Support Vector Machine (SVM)

What is SVM?

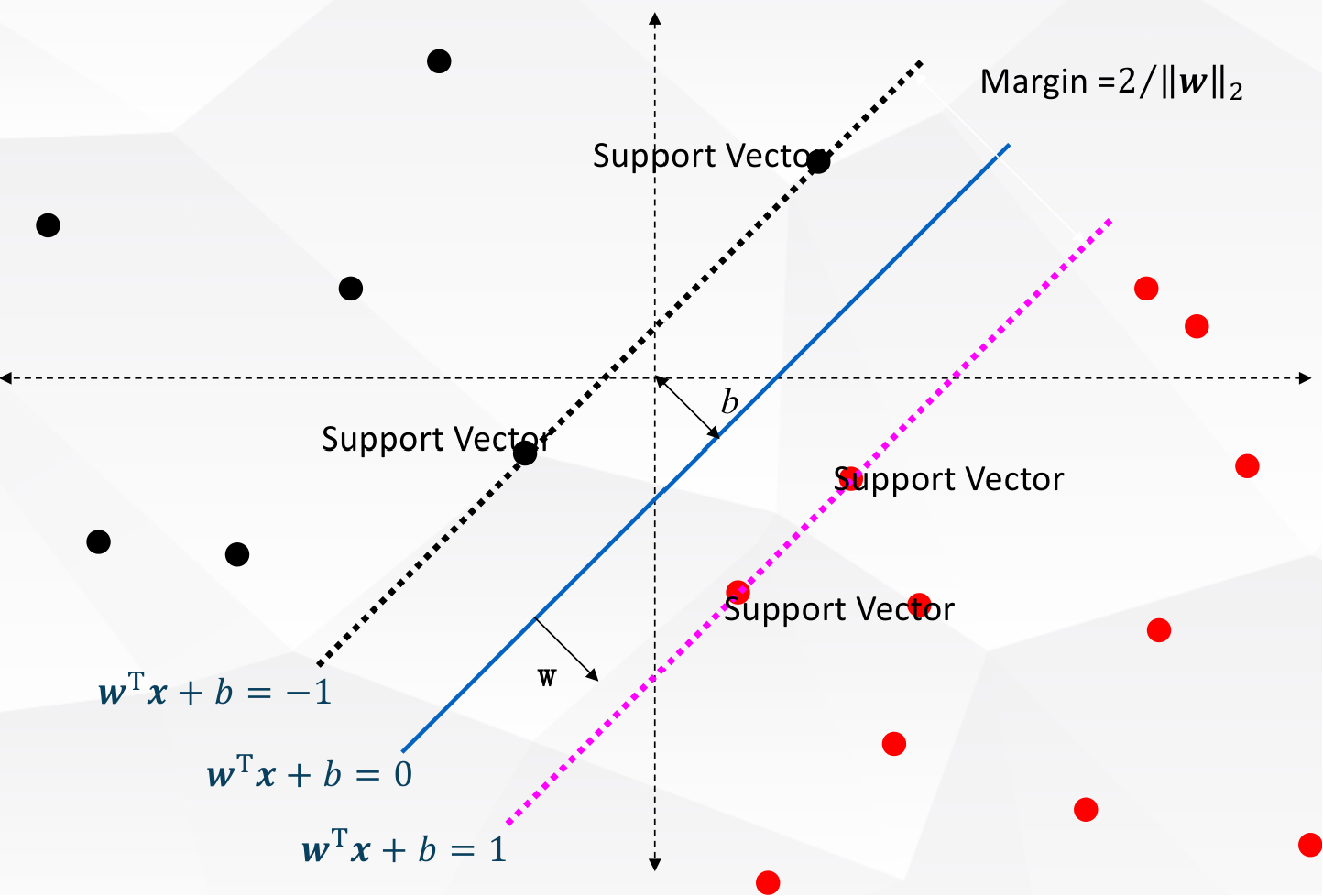

Support vector machine is a supervised learning algorithm that can be used for both classification and regression. It is a discriminative classifier, which means it tries to find a decision boundary that separates the data points into different classes.

How does SVM work?

Let linear discriminant function \(f(x)=w^Tx+b\) be the decision boundary for binary classification, where \(w\) is the weight vector and \(b\) is the bias. The decision boundary is the set of points where \(f(x)=0\).

- If \(f(x)>0\), \(y\) is expected to be \(1\).

- If \(f(x)<0\), \(y\) is expected to be \(-1\).

The biggest difference between SVM and other linear classification models is that it tries to maximise the distance between the nearest points of the two classes, which is called the margin. The points that are closest to the decision boundary are called support vectors. The vector \(w\) is perpendicular to the decision boundary, and the distance between the decision boundary and the support vectors is \(\frac{1}{\|w\|}\). The margin is \(\frac{2}{\|w\|}\).

Let \(x_p\) be a point on the decision boundary, which is the projected point of \(x\) outside the boundary, and \(\gamma\) is the distance between \(s\) and \(x_p\). Since \(w\) is perpendicular to the decision boundary,

\[\vec{x} = \vec{x_p} + \gamma \frac{\vec{w}}{\lVert \vec{w} \rVert}\]Let’s substitute \(\vec{x}\) with \(\vec{x_p}\) in the linear discriminant function,

\[\begin{aligned} f(x) &= w^Tx+b \\ &= w^T(x_p + \gamma \frac{w}{\lVert w \rVert}) + b \\ &= w^Tx_p + \gamma \frac{w^Tw}{\lVert w \rVert} + b \\ &= (w^Tx_p+b) + \gamma \frac{\lVert w \rVert^2}{\lVert w \rVert} \\ &= f(x_p) + \gamma \lVert w \rVert\\ &= 0 + \gamma \lVert w \rVert\\ &= \gamma \lVert w \rVert \end{aligned}\]In other words, the distance between the decision boundary and the support vectors is \(\frac{f(x)}{\lVert w \rVert}\). \(\gamma\) is expected to be positive, so label \(y\) can be used to eliminate the negative sign

\[\gamma = \frac{yf(x)}{\lVert w \rVert}\quad y\in\{-1,1\}\]

The minimum distance between the decision boundary and the support vectors is expected to be \(\frac{1}{\lVert w \rVert}\), since the closest point to the decision boundary is expected to satisfy \(yf(x)=1\).

The goal of SVM is to maximise the margin, which is equivalent to maximising \(\frac{2}{\lVert w \rVert}\), which is equivalent to minimising \(\lVert w \rVert^2\). The optimisation problem can be written as

\[\begin{aligned} &\max_{w,b}\frac{2}{\lVert w \rVert} \\ \text{subject to} \quad & y_i(w^Tx_i+b) \geq 1 \quad \forall i\\ \text{equal to} \quad & \min_{w,b}\frac{1}{2}\lVert w \rVert^2 \\ \end{aligned}\]SVM and Logistic Regression are both linear classification models, but they are different in the optimization, because Logistic Regression is a probabilistic model, while SVM is a geometric model.

Soft margin

The hard margin SVM only works when the data is linearly separable, meaning \(y_i(w^Tx_i+b) \geq 1\) for all \(i\). In real life, the data is usually not linearly separable. The soft margin SVM allows some data points to be on the wrong side of the decision boundary by introducing a slack variable \(\xi\).

\[y_i(w^Tx_i+b) \geq 1 - \xi_i \quad \forall i\] \[\xi_i = \left\{\begin{matrix} 0 & \text{if } y_i(w^Tx_i+b) \geq 1\\ 1 - y_i(w^Tx_i+b) & \text{otherwise} \end{matrix}\right. \geq 0\]Introducing slack variables is costly, so they must be penalised in the objective function.

\[\min_{w,b,C}\frac{1}{2}\lVert w \rVert^2 + C\sum_{i=1}^n\xi_i \\ \text{subject to} \quad y_i(w^Tx_i+b) \geq 1 - \xi_i \quad \forall i\\\]Parameter \(C\) controls the trade-off between the slack variables and the margin. When \(C\) is small, the model will try to maximise the margin, and when \(C\) is large, the model will try to minimise the slack variables. The larger the value of \(C\), the more the model will penalise the slack variables, and the larger \(\lVert w \rVert\) will be, which means the margin (\(\frac{2}{\lVert w \rVert}\)) will be smaller. When \(C\) is close to \(\infty\), the slack variables will be close to \(0\), and the model is equivalent to the hard margin SVM.

Here, \(C\sum_{i=1}^n\xi_i\) is actually Hinge Loss and \(\frac{1}{2}\lVert w \rVert^2\) is L2 Regularisation (L1 can also be used).

When \(yf(x) \geq 1\), the point is on the correct side of the decision boundary, so the loss is \(0\). When \(yf(x) < 1\), the point is on the wrong side of the decision boundary, so the loss is \(1 - yf(x)\), namely \(\xi\).

How to solve the dual problem?

The target function of SVM is actually a quadratic programming problem, which can be solved by Lagrange multipliers. The Lagrangian function is

\[L(w,b,\alpha) = \frac{1}{2}\lVert w \rVert^2 - \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_i(y_i(w^Tx_i+b)-1)\; \forall\alpha_i \geq 0\]Let

\[\theta(w,b) = \max_{\alpha_i \geq 0}L(w,b,\alpha)\]According to the dual problem, the objective function is

\[\min_{w,b}\theta(w,b)=\min_{w,b}\max_{\alpha_i \geq 0}L(w,b,\alpha)=p^*\]Here, \(p^*\) is the optimal value of the primal problem. Changing the order of \(\min\) and \(\max\), the dual problem is

\[\max_{\alpha_i \geq 0}\min_{w,b}L(w,b,\alpha)=d^*\]Here, \(d^*\) is the optimal value of the dual problem. The dual problem is always a lower bound of the primal problem, so \(d^* \leq p^*\). If \(d^* = p^*\), the solution is optimal.

The first step is to find the saddle point of \(L(w,b,\alpha)\), which is the point where the gradient of \(L(w,b,\alpha)\) is \(0\).

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial L}{\partial w} &= w - \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_iy_ix_i = 0\\ &\Rightarrow w = \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_iy_ix_i\\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial b} &= -\sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_iy_i = 0\\ &\Rightarrow \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_iy_i = 0 \end{aligned}\]The second step is to substitute \(w\) and \(b\) with the results from the first step.

\[\begin{aligned} L(w,b,\alpha) &= \frac{1}{2}\lVert w \rVert^2 - \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_i(y_i(w^Tx_i+b)-1)\\ &= \frac{1}{2}w^Tw - \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_i y_i w^Tx_i - \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_i y_i b + \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_i\\ &= \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_iy_ix_i^T\sum_{j=1}^n\alpha_jy_jx_j - \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_i y_i \sum_{j=1}^n\alpha_jy_jx_j^Tx_i - \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_i y_i b + \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_i\\ &= \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{j=1}^n\alpha_i\alpha_jy_iy_jx_i^Tx_j - \sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{j=1}^n\alpha_i\alpha_jy_iy_jx_i^Tx_j - b\sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_i y_i + \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_i\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_i - \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{j=1}^n\alpha_i\alpha_jy_iy_jx_i^Tx_j \end{aligned}\]Then, the optimazaion problem becomes maximising\(\sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_i - \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{j=1}^n\alpha_i\alpha_jy_iy_jx_i^Tx_j\) where \(\alpha_i \geq 0\) and \(\sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_iy_i = 0\).

After solving the dual problem, the optimal \(\alpha\) can be used to calculate \(w\) and \(b\).

\[\begin{aligned} f(x) &= w^Tx+b\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_iy_ix_i^Tx + b\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_iy_i(x_i^Tx) + b\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_iy_i<x_i,x> + b \end{aligned}\]where \(\lessdot\) ,\(\gtrdot\) is the inner product and \(x_i\) is the \(i\)th support vector, size of which is \(d \times 1\), and \(\alpha_i\) is the Lagrange multiplier of \(x_i\).

The KKT conditions are

\[\begin{aligned} \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \alpha_i \geq 0 \\ y_i(w^Tx_i+b)-1 \geq 0 \\ \alpha_i(y_i(w^Tx_i+b)-1) = 0 \\ \end{array} \right. \end{aligned}\]- If \(y_i(w^Tx_i+b)-1 = 0\), then \(\alpha_i > 0\).

- If \(y_i(w^Tx_i+b)-1 > 0\), then \(\alpha_i = 0\).

Optimazation of Soft Margin SVM

The optimisation target of soft margin SVM is

\[\min_{w,b}\frac{1}{2}\lVert w \rVert^2 + C\sum_{i=1}^N\xi_i \\ s.t. \quad y_i(w^Tx_i+b) \geq 1 - \xi_i,\; \xi_i \geq 0,\; C > 0\quad \forall i\]which means \(\lVert w \rVert\) is expected to be small and \(\xi_i\) is expected to be small so that more samples are correctly classified.

The Lagrangian function is

\(\begin{aligned} L(w,b,\xi,\alpha,\beta) &= \frac{1}{2}\lVert w \rVert^2 + C\sum_{i=1}^N\xi_i\\ &- \sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_i(y_i(w^Tx_i+b)-1+\xi_i) - \sum_{i=1}^N\mu_i\xi_i\\ \end{aligned}\) \(s.t. \quad \alpha_i \geq 0,\; \mu_i \geq 0,\;\xi_i \geq 0\quad \forall i\)

The first step is to minimise \(w\), \(b\) and \(\xi\), equivalently let the partial derivatives of \(L(w,b,\xi,\alpha,\beta)\) with respect to \(w\), \(b\) and \(\xi\) be \(0\).

\[\begin{aligned} \frac{\partial L}{\partial w} &= w - \sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_iy_ix_i = 0\\ &\Rightarrow w = \sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_iy_ix_i\\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial b} &= -\sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_iy_i = 0\\ &\Rightarrow \sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_iy_i = 0\\ \frac{\partial L}{\partial \xi_i} &= C - \alpha_i - \mu_i = 0\\ &\Rightarrow C=\alpha_i+\mu_i \end{aligned}\]The second is to substitute \(w\), \(b\) and \(\xi\) with the results from the first step.

\[\begin{aligned} L(w,b,\xi,\alpha,\beta) &= \frac{1}{2}\lVert w \rVert^2 + C\sum_{i=1}^N\xi_i\\ &- \sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_i(y_i(w^Tx_i+b)-1+\xi_i) - \sum_{i=1}^N\mu_i\xi_i\\ &= \frac{1}{2}w^Tw + C\sum_{i=1}^N\xi_i\\ &- \sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_i(y_i(w^Tx_i+b)-1+\xi_i) - \sum_{i=1}^N\mu_i\xi_i\\ &= \frac{1}{2}(\sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_iy_ix_i)^T(\sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_iy_ix_i) + C\sum_{i=1}^N\xi_i\\ &- \sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_i(y_i(\sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_iy_ix_i^Tx_i)+b)-\sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_i(y_i-1+\xi_i) - \sum_{i=1}^N\mu_i\xi_i\\ &= \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^N\sum_{j=1}^N\alpha_i\alpha_jy_iy_jx_i^Tx_j + C\sum_{i=1}^N\xi_i\\ &- \sum_{i=1}^N\sum_{j=1}^N\alpha_i\alpha_jy_iy_jx_i^Tx_j - \sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_iy_ib - \sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_iy_i + \sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_i\xi_i - \sum_{i=1}^N\mu_i\xi_i\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^N\alpha_i - \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^N\sum_{j=1}^N\alpha_i\alpha_jy_iy_jx_i^Tx_j \end{aligned}\]The target function is the same as the one of hard margin SVM, but the dual problem is different because \(C=\alpha_i+\mu_i\Rightarrow 0 \leq \alpha_i \leq C\).

The KKT conditions are

\[\left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \alpha_i \geq 0 \\ \mu_i \geq 0 \\ \alpha_i(y_i(w^Tx_i+b)-1+\xi_i) = 0 \\ \mu_i\xi_i = 0 \\ y_i(w^Tx_i+b)-1+\xi_i \geq 0 \\ \xi_i \geq 0 \\ \end{array} \right.\]- If \(\alpha_i = 0\), the point is not a support vector.

- If \(\alpha_i > 0\), the point is a support vector, and \(y_i(w^Tx_i+b) = 1-\xi_i\).

- If \(\alpha_i < C\), the point is on the correct side of the decision boundary, and \(\xi_i = 0\).

- If \(\alpha_i = C\), then \(\mu_i = 0\)

- If \(\xi_i \leq 1\), then \(y_i(w^Tx_i+b) \geq 0\), and the point is on the correct side of the decision boundary.

- If \(\xi_i > 1\), then \(y_i(w^Tx_i+b) < 0\), and the point is on the wrong side of the decision boundary.

What is the kernel trick?

The kernel trick is a way to transform the data into a higher dimension so that it can be linearly separable. Let \(\phi\) be the transformation function, \(d\) be the dimension of original data, and \(D\) be the dimension of transformed data.

\[\begin{aligned} f(x) &= w^T\phi(x)+b\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_iy_i\phi(x_i)^T\phi(x)+b\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_iy_iK(x_i,x)+b \end{aligned}\]The kernel function is the inner product of the transformed data:

\[k(x,z) = \left\langle \phi(x),\phi(z) \right\rangle\]And the kernel matrix is

\[K = \left[\begin{matrix} \left\langle \phi(x_1),\phi(x_1) \right\rangle & \left\langle \phi(x_1),\phi(x_2) \right\rangle & \cdots & \left\langle \phi(x_1),\phi(x_n) \right\rangle\\ \left\langle \phi(x_2),\phi(x_1) \right\rangle & \left\langle \phi(x_2),\phi(x_2) \right\rangle & \cdots & \left\langle \phi(x_2),\phi(x_n) \right\rangle\\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\ \left\langle \phi(x_n),\phi(x_1) \right\rangle & \left\langle \phi(x_n),\phi(x_2) \right\rangle & \cdots & \left\langle \phi(x_n),\phi(x_n) \right\rangle\\ \end{matrix}\right]\]Obviously, the kernel matrix is symmetric.

Common kernel functions:

- Linear kernel:

- Polynomial kernel:

- Gaussian kernel:

where \(\sigma\) is the kernel width, and \(\gamma\) is the inverse of the kernel width. The larger \(\gamma\) is, the narrower the kernel width is, the more complex the model is, and the more likely it is to overfit.

Support Vector Regression (SVR)

Let \(\epsilon\) be the error tolerance, \(\epsilon\)-insensitive loss function is defined as

\[L_{\epsilon}(y,f(x)) = \left\{\begin{matrix} 0 & \text{if } |y-f(x)| \leq \epsilon\\ |y-f(x)|-\epsilon & \text{otherwise} \end{matrix}\right.\]The objective function of SVR is

\[\begin{aligned} &\min_{w,b}\frac{1}{2}\lVert w \rVert^2 \\ \text{subject to} \quad & |y_i-f(x_i)| \leq \epsilon \quad \forall i\\ \text{equal to} \quad & -\epsilon \leq y_i-f(x_i) \leq \epsilon \quad \forall i\\ \end{aligned}\]Slack variables (positive) are introduced to allow some data points to be outside the \(\epsilon\)-insensitive tube.

\[-\epsilon - \xi_i^{\vee} \leq y_i-f(x_i) \leq \epsilon + \xi_i^{\wedge} \quad \forall i\]